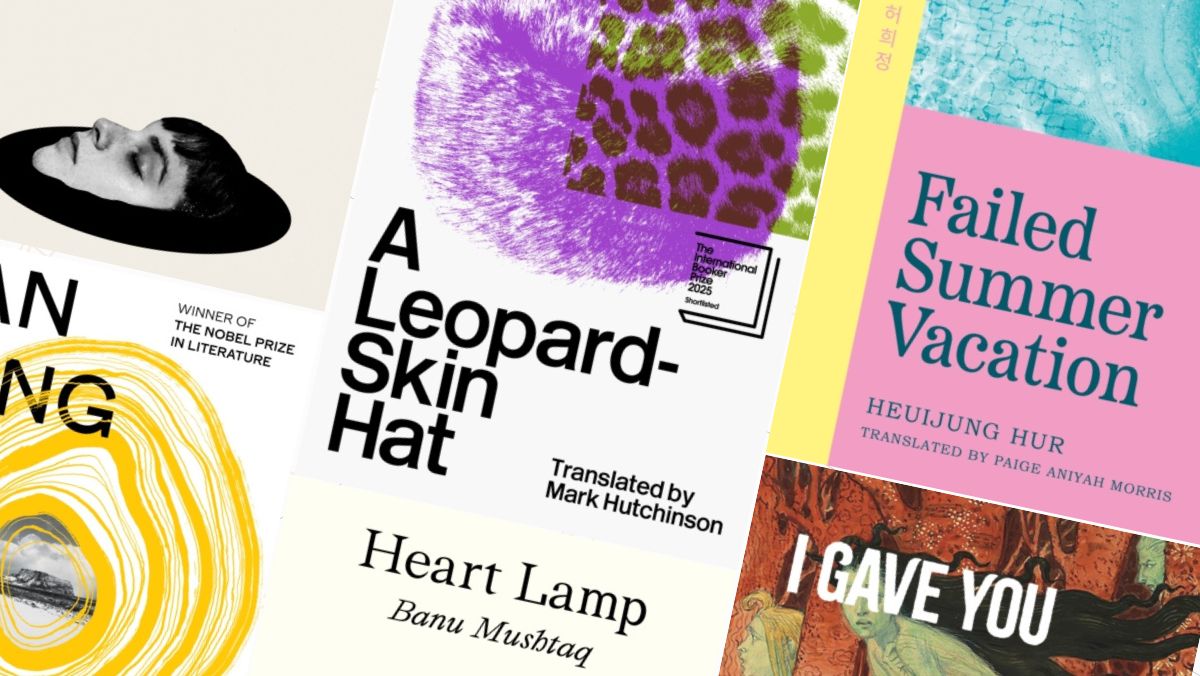

August is Women in Translation month! This your first time? If so, the rules are simple:

- Women writers

- In translation

- To read and enjoy

- During the month of August

Here’s a few recommendations: all women in translation, all recommended by real booksellers near you, a not at all comprehensive list!

A Leopard-Skin Hat, by Anne Serre (translated by Mark Hutchinson)

In the opening chapters of A Leopard-Skin Hat the narrator is attempting to eulogise his friend, a troubled young woman named Fanny, yet speaks of his inability to write something ‘realistic’, instead choosing to fictionalise her life as he remembers it. In the act of memorialisation, what purpose does narration serve when in opposition to the truth?

Through a series of vignettes, we learn of Fanny’s inherent unknowability, her contradictory nature which both liberates and exhausts the narrator, and their deep attachment to one another. Yet, despite their closeness, the narrator finds a distinct intangibility within his friend: Fanny observes her landscape with an idiosyncrasy indecipherable to many. It is this desire to understand, therefore, that prompts the narrator to create stories of his own invention.

Failed Summer Vacation, by Heuijung Hur (translated by Paige Aniyah Morris)

This collection of short stories exists – without sounding too pretentious – in a space just out of reach, at the limits of the legible imagination. Settings and plots are established, the reader is given something to grasp onto, and then the stories seemingly melt in the telling. In a future where humans no longer breathe oxygen, characters contemplate a return to the planet they abandoned. Members of a message board devoted to a controversial yet waning rock band react in strange ways to the death of one of the most prolific posters. A man made entirely of paper demands that everyone writes him a report, on pain of being pummelled with pieces of paper that shoot forth from his sleeves. If you do manage to gain a foothold in these elliptical tales, the rewards are plentiful: delicate human relationships, surreal imagery, sparse and declamatory prose, and a really good dog called Crocodile.

The Night Trembles, by Nadia Terranova (translated by Ann Goldstein)

This novel is made up of 2 intersecting narratives, both written amidst the events of the 1908 earthquake in Sicily and Calabria. One is written by Barbara, a young woman escaping an arranged marriage and navigating a new world in the wake of an unfathomable natural disaster. The other narrative imagines a paralleled reality: it follows Nicola, a boy escaping the clutches of an abusive mother, but at the cost of losing everything he has ever known. Teranova’s prose creates a poetic lacework, weaving together these intersecting lives and mirroring the devastations both characters face. From these shared stories of catastrophe there is a throughline of resilience and perseverance; a shared belief that even from complete devastation there is the possibility of a new life ahead.

Heart Lamp, by Banu Mushtaq (translated by Deepa Basthi)

Originally published in the Kannada language between 1990 and 2025, this collection of short stories trace the lived experiences of women in Muslim communities in southern India. Exposing the religious, societal, and political oppressions Banu Mushtaq witnessed in her career as a lawyer and activist, this collection is a rallying cry against the inhumane cruelty faced by those on the periphery of society. Capturing the varying textures of lived experiences, these stories are told from a variety of perspectives, from stoic mothers, cruel husbands, resilient children, and dogmatic grandmothers. From high-heeled shoes, kafans blessed with zamzam water, and pepsi mistaken for aab-e-kausar, each story immerses you in these different lives, in their different worries and priorities.

Beyond the stories themselves, the translator’s afterword, ‘Against italics’, continues to enrich the collection. Exploring Deepa Bhasthi’s approach to the translation, this post-script brilliantly frames the collection, emphasising the sensitivities and complexities of translation as a creative process.

We Do Not Part, by Han Kang (translated by e. yaewon & Paige Aniyah Morris)

It’s fair to say Han Kang is ‘having a moment’, as they say. For years she’s been a darling of the literary community, but late last year she pocketed the ultimate gong: the Nobel Prize for Literature. Few could argue that this isn’t a well-deserved accolade, as her oeuvre has somehow maintained that magical balance between accessibility and profundity, without veering too far in either direction.

And with We Do Not Part, she has created an unexpected synthesis of unsettling thriller and deeply human examination of the human condition as we all rapidly age, as well as an unconventional paean to enduring friendship and art. As our main character trudges through the thigh-deep snowdrifts on her way to her best friend’s house to feed her pet birds while she’s stuck in hospital, you’ll have no inkling of what’s in store, and you won’t guess it either and that’s how it should be.

This Room is Impossible to Eat, by Nicol Hochholczerová (translated by Julia & Peter Sherwood)

This was a captivating first introduction to Slovakian writing for me, and it’s easy to see why this book has received so much prestigious attention in its original language. Nicol Hochholczerova’s debut is a masterclass in writing the uncomfortable. In this slight, poetic coming-of-age story, themes of power, abuse, body image and shame are boldly navigated.

Spanning six years of adolescence, Tereza is groomed by her art teacher Ivan. As she navigates the obsessions of first love and her earliest sexual experiences, she is consistently let down by those closest to her, and her playful childish fantasies are gradually supplanted by adult emotions and feelings of misunderstanding.

I found This Room is Impossible to Eat to be a really stark and affecting reading experience, Despite being firmly in the realm of ‘impossible to recommend’ due to contentious and difficult themes, Hochholczerova’s is an exciting and important voice and I will be delicately placing it into people’s hands.

I Gave You Eyes And You Looked Toward Darkness, by Irene Solá (translated by Mara Faye Lethem)

Irene Sola’s second novel I Gave You Eyes and You Looked Towards Darkness feels like the cursed, uglier sibling of When I Sing, Mountains Dance. Teeming with spirits, wolves and women making pacts with the devil, it’s a book that crept under my skin and I loved it!

The novel takes place over a single day in a rural farmhouse that is alive with the ghosts of the restless women who have lived and died there over the years. As they wait for the latest living inhabitant, the impossibly old Bernadeta to join them in the afterlife, they recount the history of over 400 years of life in the house.

The women’s lives unravel in a chorus of voices, they are lives filled with pain, darkness and violence, but amongst the spite and bitterness there’s laughter and camaraderie; Sola writes with so much playfulness. It’s a feast of Catalonian folklore verging on horror, but it has a unique beauty through Sola’s vivid and poetic lens.

On the Clock, by Claire Baglin (translated by Jordan Stump)

Claire Baglin’s debut is as stirring as it is sardonic and we loved the tone of her assured, wry young narrator.

The narrative is presented in alternating passages between summers from the narrator’s childhood; camping trips with the family squeezed into the back of the Berlingo, and her summer job working in a fast food restaurant where the workplace hierarchies bring just as much anxiety as the endless order tickets.

Baglin cuts to the core of the day after day in a soulless work environment, the mechanical repetition and the petty micro-aggressions within a working team. She illuminates the struggles of soul-destroying work that thrives on exploitation. (She’s laconic, but she still has to do the work)

The nostalgic, often hilarious family memories bring a warmth – with a soundtrack of family tensions, and the neighbour’s parrot shouting about Macron in the downstairs flat, but it also portrays the struggles of working class family life, the irregular shifts

Spanish Beauty, by Esther Garcia Llovet (translated by Richard Village)

Benidorm, maybe an unexpected setting for a gritty police drama? But, it’s amongst the sunburnt holiday makers, watered-down g&ts, and all-day casinos, that García Llovet sets her new crime novel.

Spanish Beauty follows Michela McKay, a dazzling corrupt police officer searching for Reggie Kray’s cigarette lighter. Her search exposes the underbelly of the city: the Russian mafioso and English mobsters who operate beneath the swell of cheap holiday makers. Alongside its unconventional setting, Spanish Beauty is written in an experimental, playful, and slyly humorous style that continues to deconstruct the expectations of a ‘traditional’ crime novel.

Combining sandy beer bottles and abandoned g-strings with gangsters, corruption and organised crime, Spanish beauty is a cornucopia

Mammoth, by Eva Baltasar (translated by Julia Sanches)

The final part of Eva Baltasar’s triptych after Permafrost and Boulder, Mammoth is a brutal and uncompromising book. Driven by a desire to create, the narrator becomes obsessed with getting pregnant, in experiencing the physical sensations of birth. Chasing this desire, and leaving the confines of the city for the wild Spanish countryside, she enters a life of isolation and drudgery. Our narrator reduces her life to the bare essentials, collecting firewood, nursing lambs, and trying to bake her own bread. But, far from a fairytale idyll, this is a world of brutality and riotous unpredictability. In Eva Baltasars exact and poetic style, this short yet explosive book ultimately asks what it means to create in a world of loneliness and cruelty.

The Empusium, by Olga Tokarczuk (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones)

Appropriately subtitled ‘A Health Resort Horror Story’, the much-anticipated new novel from Nobel-garlanded queen of everything that is good in this literary realm Olga Tokarczuk is a gleefully sadistic tale. Assembled in the clear-aired mountains of Silesia at a dedicated ‘Guesthouse for Gentlemen’ in 1916, a bunch of doofus men with respiratory issues peck and pontificate around the case of the guesthouse owner’s recently-deceased wife. Aided by the potent local liqueur, the men become increasingly haunted, and newcomer Mieczysław battles to retain his physical and mental fortitude.

Fans of Drive Your Plow will feel a familiar unease, but the this time the terror is more pronounced, more directed, more political in its roots. Part mystery, part deconstruction of misogyny, part gung-ho horror, all Olga!

They Fell Like Stars From the Sky & Other Stories, by Sheikha Helawy (translated by Nancy Roberts)

It was a pleasure to read Sheikha Helawy’s collection of short stories documenting the quiet rebellions of Bedouin Palestinian girls and women.

From a girl’s passionate friendship with a donkey to an elderly woman’s lifelong obsession with a famous singer, Helawy’s vignettes meditate on the small-yet-determined grasps at independence made by girls and women in a society dominated by marriage and motherhood.

Helawy, who is of Bedouin Palestinian heritage, writes of the community with such warmth you feel as though you’re sitting around the dinner table, the room abuzz with noise. The characters are brave, curious, cheeky and passionate – I read the entire collection on a three-hour coach journey and audibly ‘aww’-ed at least four times at the sheer love Helawy has for her characters.

Un Amor, by Sara Mesa (translated by Kattie Whittemore)

We’ve noticed a small influx of some brilliantly dark pastoral novels by female authors recently (see: Mammoth) and if this is something of a trend then we’re wholly on board!

Un Amor is certainly one of the best of this type, translated from Spanish, it is a flawlessly crafted tale of desire and obsession. It’s the story of Nat, who flees her city life and rents a house in a small mountain town with a capricious dog that her landlord brings to keep her company. In the shadow of El Glauco and under the pointed gazes of the small community, nothing goes unnoticed, and when Nat is faced with a morally ambiguous prospect, she is forced to question her character and behaviour.

In the female pastoral novel, the values of the countryside almost appear to be flipped upside-down. The sense of freedom and isolation that comes with rural living quite quickly becomes something more sinister with a lone female protagonist, and Mesa convincingly conveys the lurking dangers and the vulnerability that’s present. A perfectly taut thriller that makes you want to slow your reading down to take in every last word.

Our Lady of the Nile, by Scholastique Mukasonga (translated by Melanie Mauthner)

A novel set in an elite girl’s boarding school might make you think of St Trinian’s or Malory Towers; girls squabbling in dorm rooms and playing pranks on their teachers. But Our Lady Of The Nile is a very different offering, with Mukasonga expertly exploring the desires and ambitions of a group of young women growing up in the epicentre of major political turmoil.

The girls who attend the lycée of Our Lady Of The Nile are in training to become the elite young women of Rwanda. Daughters of prominent businessmen and politicians, they constantly jostle for status and admiration under the watchful eye of Western teachers spouting Colonial ideals. Tensions rumble under the surface throughout, and the school itself becomes a microcosm of the burgeoning violence threatening the country.

Despite the heavy subject matter, moments of lightness and humour in the girls’ relationships make this a truly enjoyable read. The richness of Rwandan culture reveals itself in stories of queens, fortune-tellers and journeys to see the mountain gorillas, and we loved how Mukasonga weaves African folklore into the narrative.

The Bridegroom Was a Dog, by Yoko Tawada (translated by Margaret Mitsutani)

The Bridegroom Was a Dog is unapologetically weird, even for Yoko Tawada. Our main character is a schoolteacher that the town at large is already pretty suspect of, escalating dramatically when a strange man moves in with her who seems to have the soul and temperament of a dog. Throw traditional storytelling logic aside for 80 brief pages and prepare for a lot of butt humour.

Your Utopia, by Bora Chungtranslated by Anton Hur

From the author of Storysmith favourite Cursed Bunny comes another collection of whacky and disturbing short stories. Sentient cars, aliens, mad scientists: Your Utopia is the sci-fi half-sister of Cursed Bunny’s macabre horror.

all this here, now, by Anna Stern (translated by Damion Searls)

Perhaps the absolute peak of the “no plot, just vibes” genre. For some people that’s a turn off, but if you’re the kind of person who likes an all-vibe book then all this here, now is your holy grail. Composed mostly of non-chronological vignettes, each a memory in its most raw sense: tastes, smells, strange details that the mind clings to. Sounds vertigo inducing, but it’s not. More like a painting where you see each one small piece at a time, and when you stand back the whole picture reveals itself into a nuanced portrayal of friendship and grief.

FFO cathartic sadness, poetic novels

To Hell With Poets, by Baqytgul Sarmekovatranslated by Mirgul Kali

As one of the first Kazakh books translated into English, this short story introduces an English readership to Kazakh Literature and cultural geography. Each story weaves together Kazakh traditions, landscapes, auls, and tois, with something more universal, the commonality of the human condition and the strange satire of daily life. Often, the stories are set under the shadow of Soviet control and the hangover of a patriarchal system; each bears witness to a nation slowly reconciling its past with a future of commodity culture and market capitalism. These stories are all poignant and concise snapshots of life, threading together modern with the traditional, the unchanged and the unrecognisable, the melancholic with the hopeful.

A Sunny Place for Shady People, by Mariana Enriquez (translated by Megan McDowell)

We have been brimming with excitement for a new short story collection from Mariana Enriquez. Reading A Sunny Place for Shady People is like putting on an enormous comfort blanket – if, like us, your idea of comfort is a macabre place full of ghosts, supernatural beings and general terror.

Childhood friends connected by traumatic events at a site for disused refrigerators, a family inflicted by disappearing facial features, a neighbourhood driven mad by restless and angry ghosts, these stories exist just on the boundaries of what is real. The magic of Enriquez’ stories, for me, is that the settings and the characters feel incredibly real, there’s no hamming up of spooky details, and the everyday settings make the surreal elements all the more chilling. If you’re a stalwart Mariana fan, or coming to her work for the first time, A Sunny Place for Shady People is a delightfully horrifying treat.

The Earth is Falling, by Carmen Pelligrino (translated by Shaun Whiteside)

Set in an abandoned village in Naples, The Earth is Falling is fleshed out by a cast of ghosts. Each perpetually repeating their daily routines, we are given glimpses into the minds of various eccentrics including a formidable town crier. The houses themselves, and the land they stand on, seem to be alive, murmuring beneath the villagers feet. In this haunting and magical novel, past and present, dead and alive, seem to merge; as time thickens and voices overlap, Pellegrino’s echoic prose seems as alive as the village and its inhabitants.

Not a River, by Selva Almada (translated by Annie McDermott)

Set on the Paraná River in Argentina, Not a River follows the fishing trip of Enero, El Negro, and Tilo. After catching and killing a giant ray, they seem to have disturbed something, intruding upon a wider, delicate ecology of which they’re not part. The choric quality of the narration interweaves the intruder’s voices with those of the local inhabitants; in fact, Almada’s prose skillfully interweaves the past with the present, the living with the dead, the human with the animal. Annie McDermott’s translation adds to this poetic quality, creating a soundscape of half-rhymes and echoic murmurs. It’s a novel that seems to ripple, like the river that runs through it, with many undercurrents and tributaries, seamlessly connecting past and present, surface and depths.

Butter, by Asako Yuzuki (translated by Polly Barton)

This delicious combination of Japanese culture, food and murder has been tempting so many customers since publication earlier this year, and we’re happy to advocate that the Butter hype is justified.

It’s the story of a journalist, Rika, who becomes very involved in the case of convicted murderer Manako Kajii, a gourmet chef who is believed to have poisoned her past lovers. The food that Kajii cooks and consumes becomes integral to the investigations, and as Rika delves more deeply into Kajji’s story, and the rich and indulgent recipes that inspired her, her own appetite starts to awaken. Yuzuki examines perceptions about the female body, and the links between body shaming and female desire in Japanese culture. It’s a sensual read that left me feeling hungry and greasy in equal measure.

The New Seoul Park Jelly Massacre, by Cho Yeeun (translated by Yewon Yung)

Being the sensation-thirsty little book gremlins that we are, obviously we will always be attracted to a title that promises – of all things – a jelly massacre. Set it in a fictional theme park and we’re well and truly sold! We also understand that not everyone is like us, and we’re here to reassure you that this delightful Korean curio is so much more than its sensational title (and striking cover art). True enough, it does begin with a missing child in a theme park and the event that sets off the gelatinous titular incident, but the deceptive genius of the book lies in what comes next.

Zooming out from the sticky disaster of the novel’s electrifying opening, we see various perspectives on the same incident: what may have caused it, who might be most affected by it, the shadowy forces at work trying to control it. As we cycle through protagonists (including – delightfully – that of a stray cat who has made the now-abandoned theme park their home), themes of social inequality emerge, lopsided family units reach breaking point, all seemingly exhibiting a version of the same desire: to stick together, somehow. Of course, the book’s very literal response to that desire is what tips the book over into deliciously surreal territory, but it is always anchored by those very human concerns. Glibly and addictively translated into nugget-y sentences by Yewon Jung, Cho Yeeun’s hugely entertaining debut novel (there are more in her oeuvre, as-yet untranslated) is precisely as sticky as you need it to be.

The Time of Cherries, by Montseratt Roigtranslated by Julia Sanches

Published in Catalan in 1979, but only just published in English, The Time of Cherries follows several generations from the time of the Spanish Civil War to the final days of Franco dictatorship. Written with a nonlinear narrative, Roig’s plot slowly reveals itself, carefully weaving together different character perspectives. Rebelling against the slippage of time, Roig is able to unpick a country’s muddled and complex past, unthreading its changing relationships to consumerism, desire, religion, and gender.