Mountains, you might think they get enough airtime, those geographical showoffs in their provocative displays of rock and stone. But literature seems to disagree; mountains are often bypassed, overshadowed by our human narratives and stories. This list centres on books where mountains get their dues, letting them take back the limelight as characters in their own right.

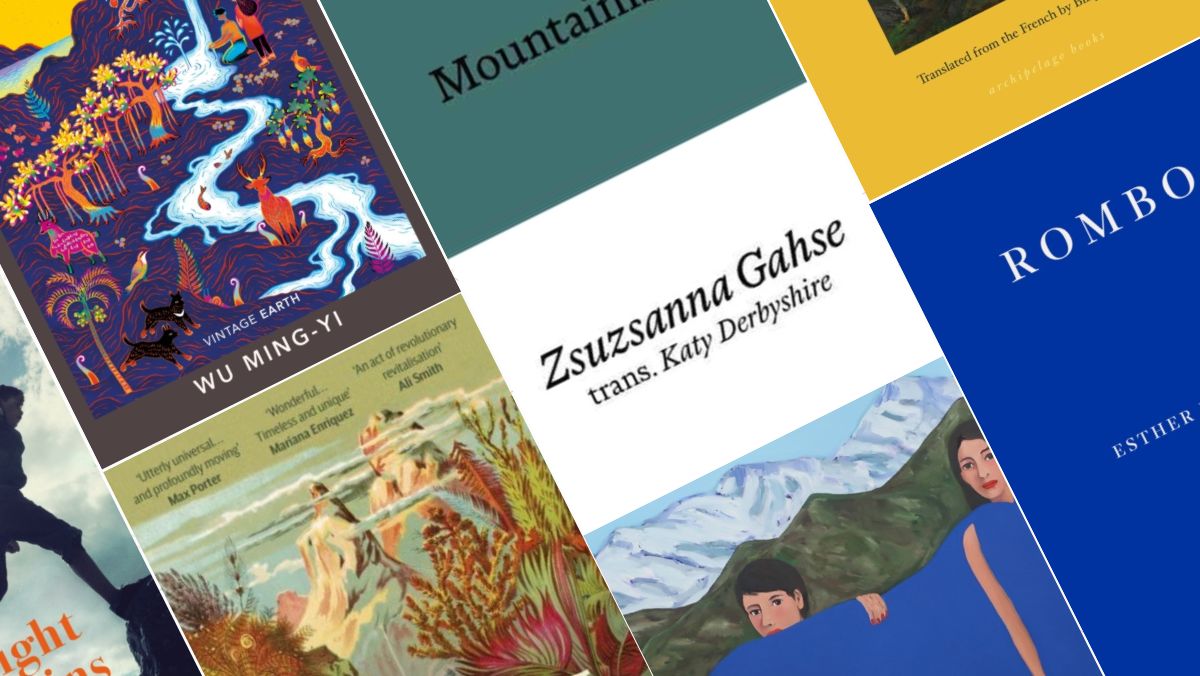

Mountainish, by Zsuzsanna Gahse, translated by Katy Derbyshire

So it’s a book about Mountains, yes. But it’s also a book about incongruities and outliers, about the ‘ishness’ of a world that can’t be easily comprehended or categorised. Even the mountains, or great ‘whoppers’ as our narrator calls them, are less sturdy and definitive than she thinks; they shift, grinding and groaning and splintering beneath her feet. She’s fascinated by the eternally alive viruses and bacteria that live deep within the rocks, or underneath glaciers waiting to break out when the ice melts.

But, most of all, it is language that frustrates her – it’s too slippery and dexterous. It fluctuates between countries, between Alpine towns and villages, and even between the mouths of two different speakers. It’s as unpredictable as mountains around her, as fluctuant and changeable.

The book, written in 515 short vignettes, plots her attempts to define and capture the mountain-scape around her with a language that continually exasperates her. What emerges is a brilliantly panoramic view of all things mountain-ish, of a world in continual motion, constantly shifting beneath our gaze.

Rombo, by Esther Kinksy, translated by Caroline Schmidt

Rombo is a book of fragments. Seven short narrative chapters, each told by an inhabitant of a mountain village in Friuli, tell the story of the Earthquakes that hit northern Italy in 1979. Each voice retells, remembers, and revisits the traumas of the event, but also gives shape to the lives, the pasts and futures, it shattered.

With the world they knew literally changing beneath their feet, these rememberings become a documentation of our amorphous, fragmented and changeable existence – of how quickly our lives can become completely unrecognisable in the hands of unpredictable natural forces. The earth itself becomes a narrator of sorts; the land speaks as an intrusive agent in our ‘human’ histories, disrupting any straightforward narrative or linear history. Aided by Esther Kinsky’s own disjointed prose style, the book becomes a sort of mosaic – a series of fragmentary pieces that collect to form a narrative whole.

Great Fear on the Mountain, by Charles Ferdinand Ramuz, translated by Bill Johnston

This story immerses us in a rural Swiss town, under the shadow of a foreboding and wildly alluring mountain.

Despite the warnings of older town inhabitants, a small group of shepherds decide to ascend the mountain to graze their cattle. But, from their very first steps, they’re met with a strange hostility – a hostility that seems to come from the very rock itself. As the story unfolds, this hostility turns into horror, despondency, and even death. Yet, it’s not the mountain’s malevolence that causes this horror – in fact, the mountain pays no real attention to the human lives under its dominion. It’s indifferent, aloof, and entirely beyond the scope of the villagers’ understandings and narratives for it.

Like its mountainous setting, Ramuz’s story also plays tricks on us, confounding expectations and straightforward plotting. Combining a mystifying setting with a haunting and poetic prose, this is a novel in which you never quite know what is coming next.

When I Sing, Mountains Dance, by Irene Sola, translated by Mara Faye Lethem

This book begins amidst a downpour, amidst the rainclouds, complaining of their full bellies, burdened with water, lightning and and thunder. In the course of their rumblings, they knock down a farmer, Domènec, with a lightning bolt, killing him on the spot.

From here, the narrative falls back down to earth, following Domènec’s family, their grief, and the ghosts that continually disturb their lives. But it is not only human ghosts that disrupt this narrative; the Pyrenees mountains make their presence continually felt, roiling the human narratives with interruptions of their own. The land, the animals that inhabit it, even the mushrooms that spawn from it, all have the chance to narrate their own stories. Rippling with human and more than human narratives, When I Sing, Mountains Dance is a story of overlapping histories, agencies, and consciences, all coalescing to form an evocative portrait of Catalonia and its inhabitants.

The Night Trembles, by Nadia Terranova, translated by Ann Goldstein

This novel is made up of two intersecting narratives, both written amidst the events of the 1908 earthquake in Sicily and Calabria. One is written by Barbara, a young woman escaping an arranged marriage and navigating a new world in the wake of an unfathomable natural disaster. The other narrative imagines a paralleled reality: it follows Nicola, a boy escaping the clutches of an abusive mother, but at the cost of losing everything he has ever known. Teranova’s prose creates a poetic lacework, weaving together these intersecting lives and mirroring the devastations both characters face. From these shared stories of catastrophe there is a throughline of resilience and perseverance; a shared belief that even from complete devastation there is the possibility of a new life ahead.

Ghost Mountain, by Ronan Hession

This was my first encounter with Ronan Hession’s work, and I now want to go back and read everything he’s written! Here, he tells the story of Ghost mountain, a mountain that appears overnight on the outskirts of an unremarkable town. Yet, rather than focus on this seismic event, Hession’s story centres on the human lives that surround it. Rather than making the mountain mean something, Ghost Mountain becomes the empty centre at the heart of the novel: an invisible force, an agent in the minutiae of the human lives that live in its shadow. As Hession keeps repeating ‘Ghost Mountain was Ghost Mountain.’

The Empusium, by Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Appropriately subtitled ‘A Health Resort Horror Story’, the much-anticipated new novel from Nobel-garlanded queen of everything that is good in this literary realm Olga Tokarczuk is a gleefully sadistic tale.

Assembled in the clear-aired mountains of Silesia at a dedicated ‘Guesthouse for Gentlemen’ in 1916, a bunch of doofus men with respiratory issues peck and pontificate around the case of the guesthouse owner’s recently-deceased wife. Aided by the potent local liqueur, the men become increasingly haunted, and newcomer Mieczysław battles to retain his physical and mental fortitude. Fans of Drive Your Plow will feel a familiar unease, but this time the terror is more pronounced, more directed, more political in its roots. In fact, this unease seems to emanate from the mountainous setting that holds the guesthouse, a natural world completely beyond the intellectual reach and pontifications of these men. Part mystery, part deconstruction of misogyny, part gung-ho horror, all Olga!

Strega, by Johanne Lykke Holm, translated by Saskia Vogel

This sharp and unsettling little novel reads like a dark and beautiful fairytale. In a grand hotel in a small Alpine village, nine girls learn to clean, cook and serve guests under the watchful eyes of stern and unforgiving matrons. As the season progresses and no guests arrive, the girls grow closer and closer until, when one of the group suddenly disappears, they are forced together, pack-like against the threats of the outside world. Johanne Lykke Holm’s prose is completely bewitching and the fresh mountain backdrop coupled with such a dark and twisty tale creates something truly special.

The Eight Mountains, by Paolo Cognetti, translated by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell

This novel promises to transport you joyfully to the Italian mountains, and the breathless expanse of the alpine air.

Pietro is a city boy who spends his childhood summers in the rural foothills of the Italian Alps. He develops a friendship with Bruno, a local farm boy who is very connected with the land, and the two boys spend their summers exploring the hills and valleys of their mountain playground. As the years go by, Bruno’s father’s obsession with scaling the most difficult peaks starts to drive a wedge between them, and Pietro is drawn away from the mountains, only to be called back time and time again.

The beautiful simplicity of Cognetti’s language unfolds into a bildungsroman with a powerful focus on complex relationships, enduring friendships, and the power of nature to transform us in both positive and negative ways. It’s a cliché, but the landscape really is a character in this novel – one you’ll feel just as involved with and as the protagonists.

The Man with Compound Eyes, by Wu Ming-Yi, translated by Darryl Sterk

Many, many disparate threads (including but not limited to a semi-mythological island society called Wayo-Wayo, a floating archipelago of ocean garbage, mountain tunnel construction, traditional whaling practices, language acquisition) wind their way together to form a richly textured, superbly translated fable of climate change, Taiwanese culture and myth. Heavy dollops of narrative fiction, eco-fiction with a subtle veneer of the supernatural. Delicious!