Works that comb the farthest reaches of this wide-ranging continent, not just the sun-soaked city break bits.

all this here, now. by Anna Stern translated by Damion Searls

Perhaps the absolute peak of the “no plot, just vibes” genre. For some people that’s a turn off, but if you’re the kind of person who likes an all-vibe book then all this here, now is your holy grail. Composed mostly of non-chronological vignettes, each a memory in its most raw sense: tastes, smells, strange details that the mind clings to. Sounds vertigo inducing, but it’s not. More like a painting where you see each one small piece at a time, and when you stand back the whole picture reveals itself into a nuanced portrayal of friendship and grief. FFO cathartic sadness, poetic novels

Money to Burn, by Asta Olivia Nordenhof (translated by Caroline Waight)

I was immediately hooked on the concept of this book. It’s the first in Nordenhof’s Scandinavian Star series, named after a fated passenger ferry that caught fire in 1988 killing 159 people. It’s impossible not to be instantly intrigued by the family that Nordenhof creates in Money to Burn, and their complex and unconventional relationships.

Nordenhof’s elusive narrator introduces us to Kurt and Maggie, a married couple whose daughter has recently left home, leaving them adrift in their lives and distant from each other. In shifting perspectives and jumps back and forth in time, we piece together the history of this couple and the turbulent, often violent story of their relationship. The tragedy of the Scandinavian Star connects very loosely to Kurt and Maggie’s story, but there’s a sense that, in Money to Burn, Nordenhof has laid the foundations for a complex family saga with a looming capitalist threat. I love Nordenhof’s controlled prose and the moments of searing sensitivity that really cut to the heart. I’ll be waiting impatiently for September to see where she takes us next!

Living Things, by Munir Hachemitranslated by Julia Sanches

As the narrator in Living Things tells us, “Terror is always a soft, sticky thing and never something effusive, never an explosion.” The slow-moving violence in this novel are the veiled horrors of the agri-food industry, environmental breakdown, and the corruption of conglomerate capitalist corporations. These concealed horrors undercut this eco-thriller, reverberating across pages. The story follows four young Spaniards who have travelled to France and end up working on poultry farms. These four friends, one of whom is our narrator, are obsessed with collecting experiences, with following a story to its messy, and sometimes grotesque end. It is this play between the search for employment and the search for a story, the currency of capital and the currency of literature, that also makes this book so impressive. All of this, interwoven in a slim novel (of just over 100 pages), makes Living Things a compelling, gripping read.

The Time of Cherries, by Montserrat Roigtranslated by Julia Sanches

Published in Catalan in 1979, but only just published in English, The Time of Cherries follows several generations from the time of the Spanish Civil War to the final days of Franco dictatorship. Written with a nonlinear narrative, Roig’s plot slowly reveals itself, carefully weaving together different character perspectives. Rebelling against the slippage of time, Roig is able to unpick a country’s muddled and complex past, unthreading its changing relationships to consumerism, desire, religion, and gender.

Verdigris, by Michel Maritranslated by Brian Robert Moore

We’re still reeling from Verdigris, Michele Mari’s darkly comic gothic novel.

It is the summer of 1969, and thirteen year-old Michelino spends his summer day trawling his grandparents’ estate in the Italian countryside, often in the company of Felice, the cantankerous groundskeeper. When Felice starts to lose his memory, Michelino is tasked with not only coaxing those memories back into existence, but also reconfiguring what it means to belong.

Mari is a widely-acclaimed master of lexicon, and Verdigris is no exception to this; language becomes almost-Frankensteinian as words are pulled apart and stripped bare, with Michelino feeding his ‘creature’ these new notions of existing. The use of wordplay and imagery is head-scratchingly clever and masterfully retained in Brian Robert Moore’s translation.

With creepy doors, cowboy films and flesh-eating slugs, this novel is sad and kooky and perfect for anyone keen on linguistic gymnastics.

Mammoth, by Eva Baltasar translated by Julia Sanches

The final part of Eva Baltasar’s triptych after Permafrost and Boulder, Mammoth is a brutal and uncompromising book. Driven by a desire to create, the narrator becomes obsessed with getting pregnant, in experiencing the physical sensations of birth. Chasing this desire, and leaving the confines of the city for the wild Spanish countryside, she enters a life of isolation and drudgery. Our narrator reduces her life to the bare essentials, collecting firewood, nursing lambs, and trying to bake her own bread. But, far from a fairytale idyll, this is a world of brutality and riotous unpredictability. In Eva Baltasars exact and poetic style, this short yet explosive book ultimately asks what it means to create in a world of loneliness and cruelty.

Time Shelter, by Georgi Gospodinovtranslated by Angela Rodel

Winner of the International Booker 2023, Time Shelter furnishes a ‘clinique of the past’, a kind of hospice that transports patients back in time to decades past. Yet, as these nostalgic retreats become increasingly high demand, a lust for the past seeps into the wider world. Infact, the novel itself becomes a jumble of past and present, and temporal confusion. Time shelter offers a cutting and polemical take on an increasing obsession with the past and its impact on personal and national identities.

Eurotrash, by Christian Kracht (translated by Daniel Bowles)

Translated from the original German, Eurotrash follows the misadventures of a middle-aged writer and his elderly mother, and begins with the promising prospect of the duo travelling in the back of a taxi through the Swiss Alps with wads of cash in their pockets and surviving on a diet of vodka and phenobarbitals.

This impromptu trip is a feeble attempt to rid themselves of their ill-gotten fortune, and to assuage some portion of the guilt they feel in relation to the chequered past they share. As they travel through a series of calamitous situations, mother and son argue and bicker and berate each other. But despite their bitterness, care and tenderness shines through. Kracht explores the emotional impact of caring for an ageing parent, and the strong connections between them (that go deeper than their shared love of cashmere).

If you’re willing to go with a few delightfully convoluted historical jags, the reward is that Kracht always makes sure to plunge you right back into the madcap action, making Eurotrash a thrilling whirlwind of a novel: a cleverly written reflection on ageing, wealth and privilege which, despite some savagery, still manages to be oddly poignant.

The Annual Banquet of the Gravediggers’ Guild, by Mathis Enard translated by Frank Wynne

David Mazon, an anthropology student from Paris, moves to La Pierre-Saint-Christophe; this French village is deeply immersed in religious belief, spirituality, and mysticism. This seemingly unbecoming and barren land is increasingly revealed to be alive with a ‘vast spider’s web of souls’; human and more than human lives are entwined in a cyclical movement of life and death, decay and regrowth. Drawing from the repositories of the past, Enard’s prose is also inspired by French history and literary tradition; while some chapters are written in a contemporary, epistemological style, others mirror a rabelaisian wit and bawdry. Enard interlaces the veins of History, overlapping the past and present, and entwining souls both human, animal, and microbial.

When I Sing, Mountains Dance by Irene Solà (translated by Mara Faye Lethem)

This gorgeous, lyrical novel tells the stories and histories of a mountain community through the voices of the families that live there, the roe deer, the chanterelles, the raindrops, the witches and the ghosts that hover over the landscape. Through stories and observations we piece together the love and loss and sufferings of one family, and their connections with the wild and beautiful nature that surrounds them. A clever and truly beautiful book that I wanted to start again immediately after finishing!

Star 111, by Lutz Seiler

(translated by Tess Lewis)

“Disintegration was promise, not death, just life, that was the paradox of the time”; so thinks Carl, the protagonist of Star 111.

Set after the fall of the Berlin wall, the novel maps the movement of disintegration and German unification. Carl, a bricklayer, literally helps reconstruct the broken world around him, yet finds means to reconstruct family, community and his own identity as a poet. Inhabiting the city’s underground bars, anarchist cafes, and abandoned buildings, Star 111 is a novel alive with ideas and possibility. Through incantatory, and sometimes mystical, prose, Seiler’s very language mirrors a world in process, making new laws and meanings for itself.

Strega, by Johanne Lykke Holm

(translated by Saskia Vogel)

This sharp and unsettling little novel reads like a dark and beautiful fairytale. In a grand hotel in a small Alpine village, nine girls learn to clean, cook and serve guests under the watchful eyes of stern and unforgiving matrons. As the season progresses and no guests arrive, the girls grow closer and closer until, when one of the group suddenly disappears, they are forced together, pack-like against the threats of the outside world. Johanne Lykke Holm’s prose is completely bewitching and the fresh mountain backdrop coupled with such a dark and twisty tale creates something truly special.

The Sky is Falling, by Lorenza Mazzetti (translated by Livia Franchini)

It’s hard to resist this beautiful package that’s been firmly on our recommends shelf since it arrived. A tiny novel from Lorenza Mazetti, bound beautifully with illustrations from the author’s notebooks, translated by Livia Franchini and with an introduction from Ali Smith, it is literally a dream collaboration.

Moonstone by Sjón

(translated by Victoria Cribb)

Sjón is a brilliant writer and Moonstone is a great place to start with his work and with Iceland’s literary scene as a whole. Moonstone is a queer, ethereal novel set at the cusp of Icelandic independence, the birth of surrealist cinema and the height of the 1918 pandemic. Serious and playful in equal measure.

The Appointment, by Katharina Volckmer

Caustic and sharply hilarious, this merciless and perfectly formed novelette is one brilliant monologue, the results of a woman’s single appointment with her doctor – expect blazing ruminations on shame, sex and squirrel tails.

Love, by Hanne Ørstavik

(translated by Martin Aitken)

In the course of a single evening, a mother and son experience wildly different emotional truths as they go about their separate lives: the son, on the eve of his birthday, is waiting for his mother to return from the shops with birthday cake ingredients, while she takes a turn past the travelling funfair to meet a man. Sparse, dark and tense, this is a relationship in microcosm, a beautiful dissection of bigger themes than its humble pages suggest.

The Discomfort Of Evening, by Lukas Rijneveld (translated by Michele Hutchison)

The stink of the cowshed and the hard bite of the frozen winter ground stalk this utterly unique (and deservedly prizewinning) novel from a Dutch debutant. A young girl and her family suffer a tragedy, and the effects spread deeply into their lives, and in increasingly disturbing ways. Written in that horrid sweet spot between innocence and experience, there’s a surprisingly large amount of humour here, too.

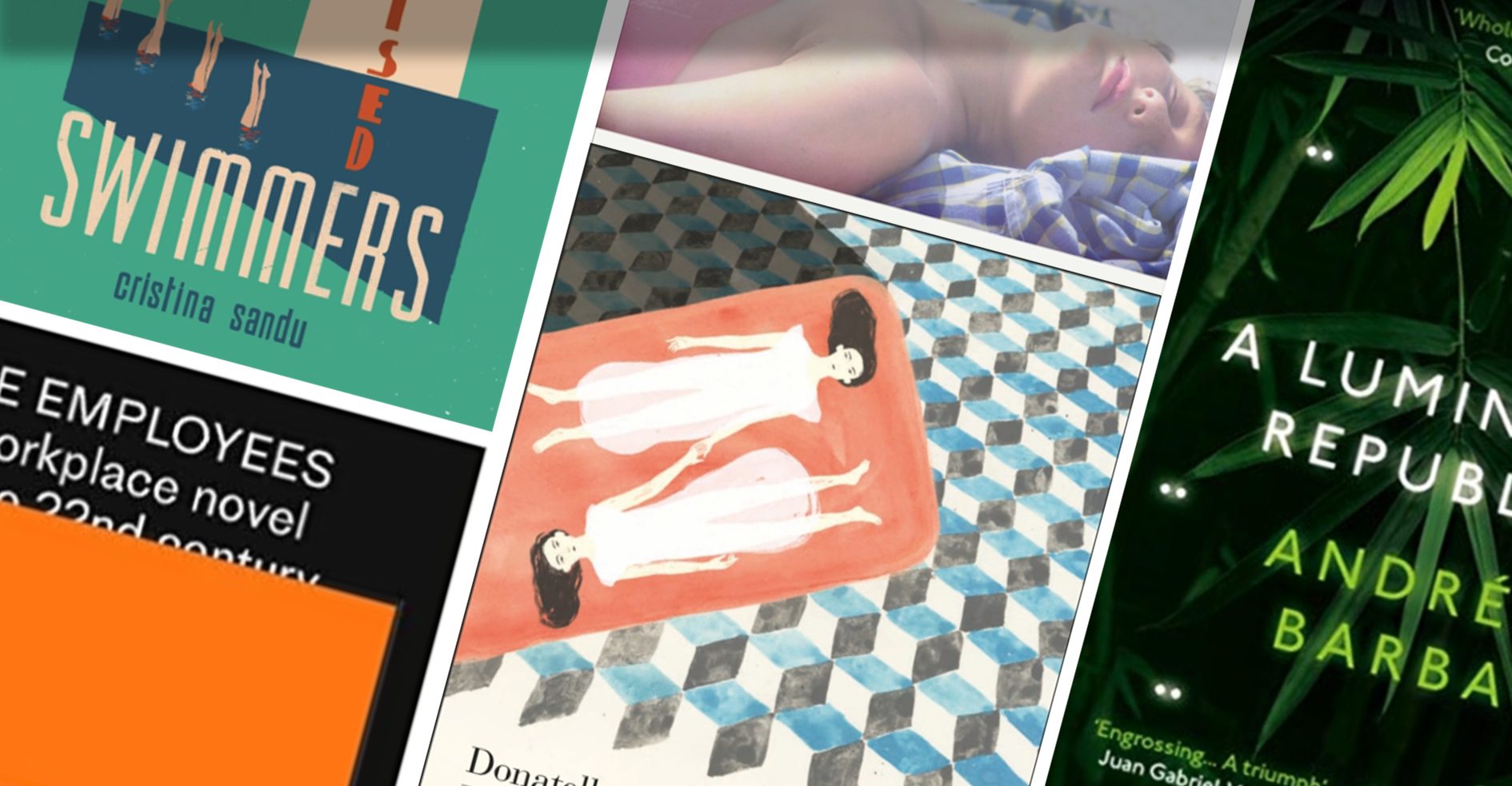

A Luminous Republic, by Andrés Barba (translated by Lisa Dillman)

A city is overrun by children, unwashed and speaking their own distinct and invented language. They turn nasty, and there are consequences. This claustrophobic, sweaty and disturbing found-document-style novel from Spanish novelist Andrés Barba gracefully yet mercilessly asks us to consider how powerful children really are, and how powerful adults are willing to be to contain them.

Flights, by Olga Tokarczuk

(translated by Jennifer Croft)

Flights is less straightforwardly a novel and more a “novel of novels”… or a novel of novelettes? Some chapters are the brief musings of a lone traveller in an airport, while others are deep-dives into a story from a fragmented corner of European history, all brought together into a compelling meditation on bodies in motion, and the human need to travel, cross boundaries, transgress.

A Girl Returned, by Donatella Di Pietrantonio (translated by Ann Goldstein)

A young girl is taken away from her family as a baby, and then returned to them as a teenager and – more importantly – a stranger. This tiny blitz of a story (from the translator of Elena Ferrante’s classic novels) is wrought with family tension, class divisions and the intensity of teenage emotion.

The Employees, by Olga Ravn

(translated by Martin Aitken)

A fragmentary novel told through unlabeled and uncategorised statements from employees of the Six-Thousand Ship, a spaceship on an unknown task in the far-flung depths of the galaxy. Out of these interviews, Olga Ravn constructs a subtle and beguiling novel, probing questions of intimacy, humanity, and the future of human labour in a non-human future.

At Night All Blood is Black by David Diop (translated by Anna Moschovakis)

This is not your standard war book. At Night All Blood is Black is a blistering confessionary tale of one man’s descent into his own psyche, and a mesmerising but gruesome novel of revenge.

Bonjour Tristesse, by Francois Sagan

To us Bonjour Tristesse is a perfect summer novel. Truly atmospheric, it conjures the shimmering heat and glamour of the Côte d’Azur in the height of summer. Seventeen year old Cécile and her widowed father rent a holiday home with his latest young and beautiful girlfriend to enjoy a summer of bathing, tanning and carefree langour. A masterful study of manipulation, power-plays and guilt, it’s a novel that you can devour in one sun-soaked sitting, but it will stay with you long after you’ve finished reading.

The Union Of Synchronised Swimmers, by Cristina Sandu (translated by Cristina Sandu)

This slight and clever novel from a Finnish-Romanian debutant follows six women who are destined to become Olympic synchronised swimming champions. But as they relentlessly train their bodies in the lake of an unnamed Soviet state, it is freedom that they really hope for. Subtle, moving and simply told.

Mountainish, by Zsuzanna Gahse (translated by Katy Derbyshire)

So it’s a book about Mountains, yes. But it’s also a book about incongruities and outliers, about the ‘ishness’ of a world that can’t be easily comprehended or categorised. Even the mountains, or great ‘whoppers’ as our narrator calls them, are less sturdy and definitive than she thinks; they shift, grinding and groaning and splintering beneath her feet. She’s fascinated by the eternally alive viruses and bacteria that live deep within the rocks, or underneath glaciers, waiting for the ice to melt to break out. But, most of all, it is language that frustrates her definition; it’s constantly switching meanings or metamorphosising, fluctuating constantly between towns and villages, between the mouths of different speakers.

The book, written in 515 short vignettes, plots her attempts to capture and categorise the mountainscape around her. What emerges is a brilliantly panoramic view of all things mountainish, of a world constantly shifting beneath our gaze.